Some thoughts on grief

September 11, 2022

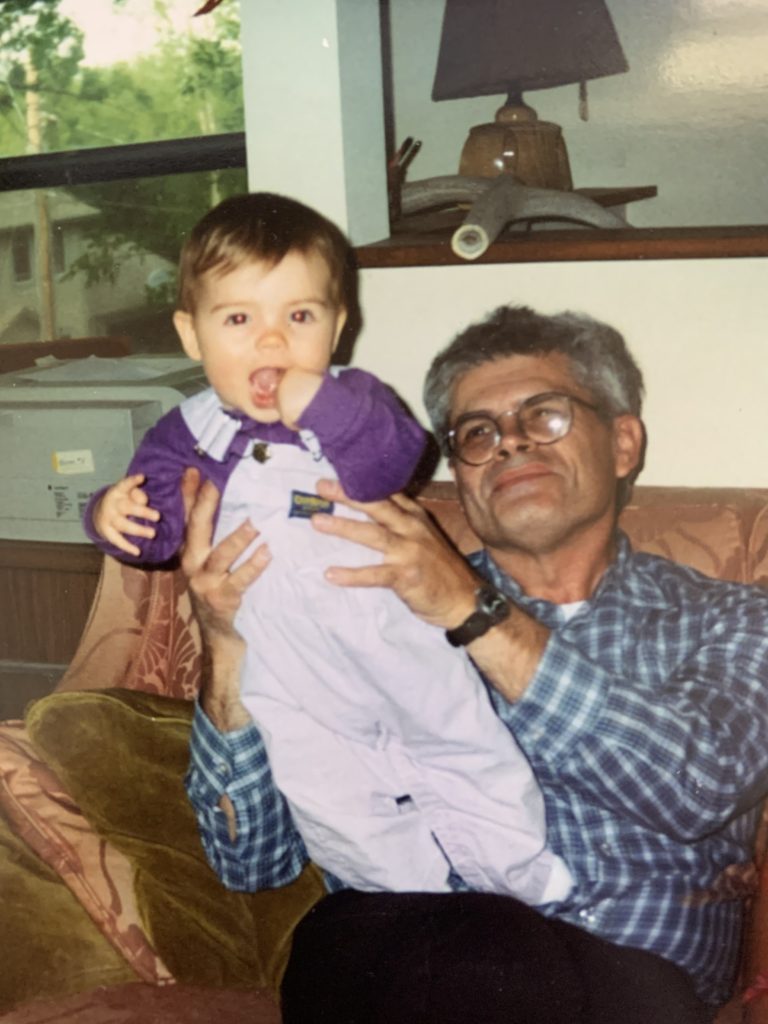

My dad, Jim Conover, died this summer. On June 30, a Thursday. He was 78, and it was unexpected — yet to be expected, as death is.

If I’ve learned anything in the last few months, it’s that it’s grief which is nothing like I expected it would be.

However grim or morbid it makes me sound, because my parents were both older than average when I was born, I’ve always been sensitive to the fact that I might not be granted as much time with them as a daughter could typically count on.

Fairness isn’t part of life, we have no promise of anything but the end. Still, it doesn’t change the fact that 26 years with a parent is not enough time.

I had imagined what it would feel like to get that news. How I would handle it. How life would change, or how much I would cry.

The truth is, you can’t prepare for such things. You have no control over how hard something hits you. And every time a wave of grief rolls in, I’m struck once again by how unprepared I was — I am.

Grief is easiest in the shower. The hot water takes your tears for you. It massages your skull and lets you stare mindlessly at the tile pattern for who knows how long. Eventually though, the water runs cold.

Some days, it’s sitting in the car, singing along with a raw, shaky voice to a playlist carefully curated to dredge out the tears. Other days, it’s vigilantly avoiding anything that might stir the slightest emotion.

It’s clenching your jaw so hard you think your teeth might crack, just so you don’t sob in certain situations. Watching a movie with something unexpectedly bothersome. In the coffee shop when an older man walks in. At the graveside — though there your jaw betrays you, no matter how hard you try.

It’s desperately wanting to talk about the person — the good and the bad — just to keep their memory fresh in your mind.

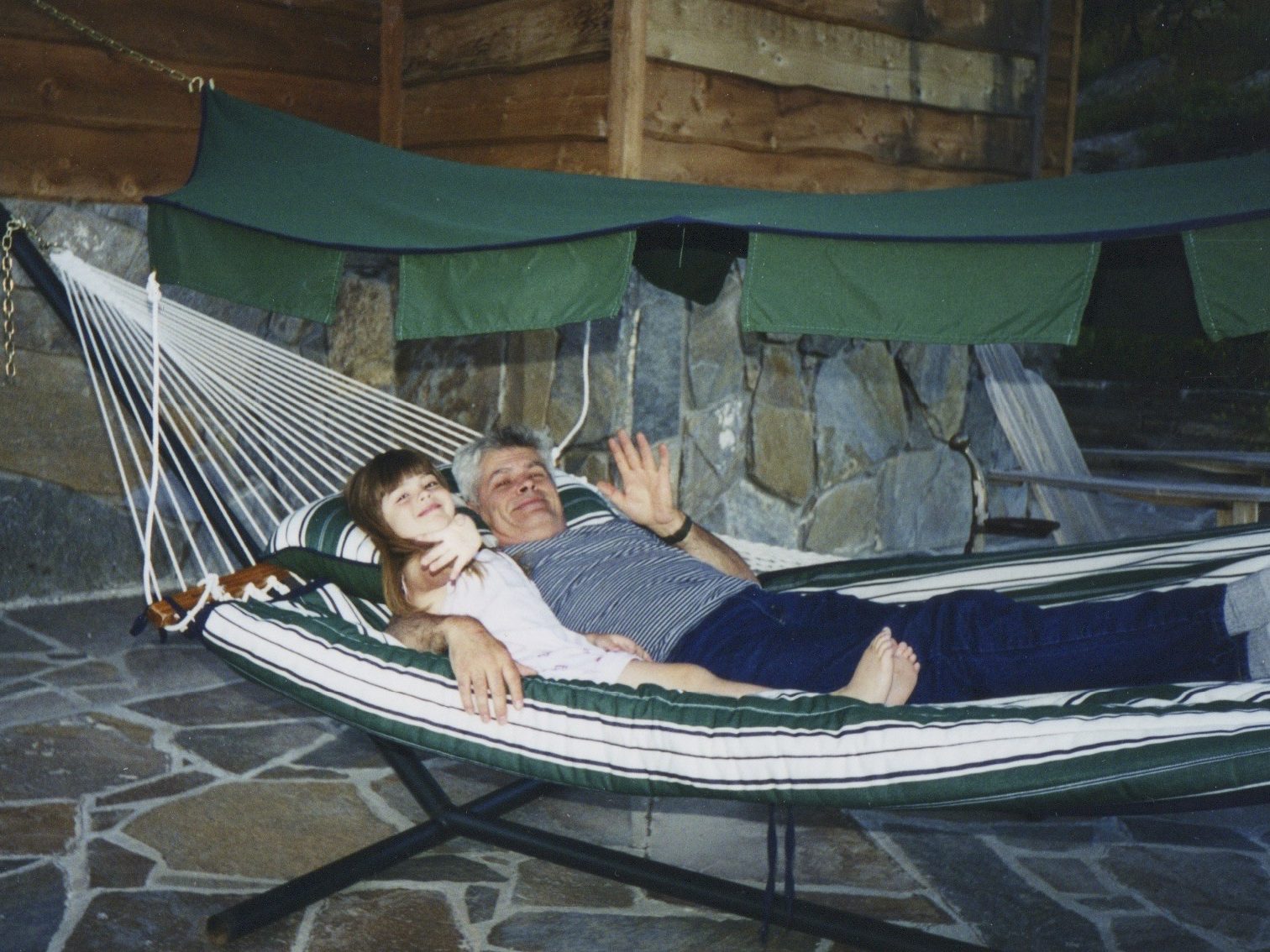

Lying in bed long after your husband has fallen asleep, staring at old photos on your phone until your eyes go blurry.

Sometimes, it’s anger or frustration, because not everyone says or does the right things. Usually, you can’t blame them. But other times you can, and that stings the deepest.

It’s feeling like you don’t recognize the new you who’s living with this grief — while, simultaneously, feeling more yourself than you have in a long time, because you’re noticing, more than ever before, those parts of yourself they gave you.

It’s recognizing that memories are never complete reality. But at the same time, they’re all you have for now.

There are beautiful, good, sunny days. Hugs from friends, walks with your dog, the love of your husband, your sister, your mom. Days when you’re sure life has gone back to normal. And in a way, it has, because those sunny days come more and more often as time passes. But the hard days, or hours, or moments, still come.

You realize that this is life. And that’s a comfort, in its own way. You release the pressure to be “done” with grief and allow it to settle into its place. It’s a part of you now — but more to the point, the person you love is part of you now. You get to carry them with you.

In the haze of that first week after he died, I wrote both his obituary and a eulogy. Somehow, I managed to give the latter at the funeral.

a eulogy for my dad, Jim:

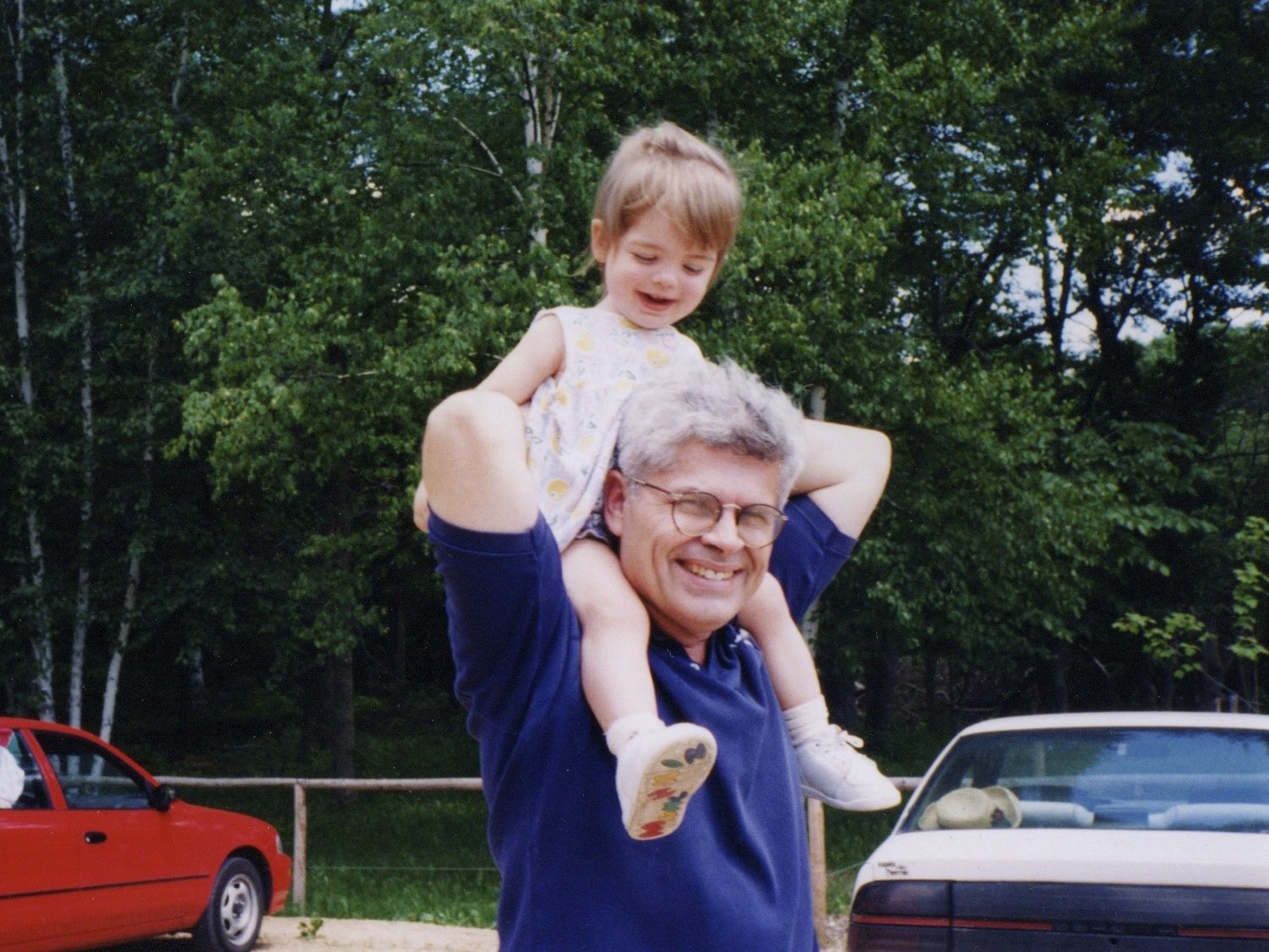

When I was little, Dad would wake me up early on Saturdays for what he called “real life adventures.”

We would drive into the city in his Jeep. It had the most specific smell—this perfectly Dad blend of sawdust and cigarette smoke—and he always had some sort of hard candy for me, Neccos or butterscotch or Life Savers. He would take me to museums or art supply stores or furniture showrooms, and point out good design, lecture on the merits of certain colors and materials, and simply observe, always on the hunt for the interesting and unusual. Then, he would bring me to some hole-in-the-wall restaurant, where I would have to try things that challenged my picky taste buds.

On the way home though, I was usually rewarded with a stop at Lunds, where we would pick up treats more to my liking. A loaf of crusty French bread, which we would tear pieces off of in the car to snack on. A box of popsicles or Haagen Dazs coffee ice cream. And usually a cup of olives or herring from the salad bar—but those were for him.

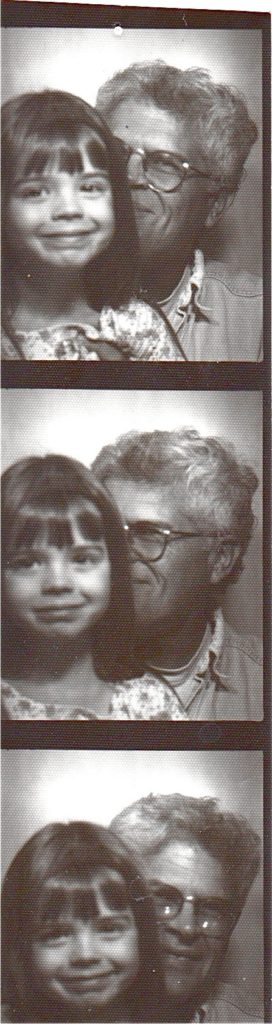

I always loved our time together. Dad knew how to make you feel special. Like you were the only two in the room who “got it.” With a twinkle in his eye or a sly wink, we shared many an amusement or observation, just between us.

He was nothing like any of my friends’ fathers, and though I didn’t always know what to make of it, I knew how much he loved me and was often thinking of me..

As I got older and we weren’t under the same roof anymore, he would call at the most random times, just to tell me he’d been watching PBS or listening to the radio and that I just had to look up some artist or song or book title— he always had little bits of cultural wisdom to share. But more often than not, it was that he’d been listening to the weather and heard there were storms or snow in the forecast — he’d say, “you’re not driving anywhere, right, Ann?”

It was that same offbeat, but still somehow spot-on, thoughtfulness with gifts. He would show up to holidays, or just any old day, with the most random items for me, some old jacket from a thrift shop or a trinket he’d picked up off the side of the road—what might look like trash to anyone else but had made him think of me because the color was just right for my eyes.

My teenage self didn’t always wear the clothes he found for me, but now, when I consider the things I’m drawn to, I see so clearly how his eye has guided me over the years. I know it always will.

I showed up a bit later in life—Dad was 51 when I was born—so I know there are countless stories and details I don’t have firsthand. I would love for you to share them with me.

Hi, I'm Andrea!

What do you love? For me, it's hearing a good story, working in my garden (during the few warm months we get here in South Dakota), cozying up to watch a movie, and hanging out with my husband, my friends, and my cuddly pup, Nessie.

Oh, and I'd love to meet you, too!

This is beautiful Andrea. You do get to carry him through your life. Life is like two train tracks – the good and beautiful and normal right alongside the grief and the hard.

Your dad lives on in you as you share your gift as a writer and “knower” of tasteful, artistic, classic and quirky things with everyone who knows you.

Love, Jana